-

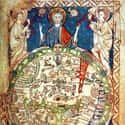

(#1) T-O Map From Isidore Of Seville's 'Etymologies,' Circa 600

Many medieval world maps followed the same general style, known as the T-O map. These maps showed the three known continents in a T-shape, ringed by an O of water - sort of like the Trivial Pursuit wedge of the world. This simplified version of a medieval world map emphasizes the simple shape of the world in its lines.

Asia is shown at the top of the map, with Europe and Africa below. The Mediterranean, the Nile, and the River Don make up the water separating the continents.

This style of map, which didn’t prioritize accuracy, was meant to highlight the harmonious balance between the continents. It was also clearly a religious map: Jerusalem was at the center, and mapmakers often included religiously significant items, such as Noah’s Ark or the Earthly Paradise.

-

(#2) Psalter World Map, Circa 1265

Just in case the religious nature of the map isn’t clear, the Psalter Map, made in the 1260s, drives the point home by placing a giant image of Jesus on top. This small map, measuring only 6.6 inches high, was painted in a 13th-century copy of the Book of Psalms. In addition to Jesus holding court over the world, the Psalter Map places a large bull's-eye over Jerusalem at the center.

Mythical monstrous people inhabit the right side of the map, while the Red Sea is actually painted red. But these monsters are not just figments of the unknown mapmaker’s imagination: they are based on classical texts like Pliny the Elder’s Natural History. Pliny claimed a North African tribe was “said to have no heads, their mouths and eyes being seated in the breasts.” Here, Pliny’s classical tales mix with biblical knowledge on one map.

-

(#3) Tabula Peutingeriana, 1265

The Tabula Peutingeriana, an itinerary map, is a reproduction of a Roman map, showing the highways of the Roman world all the way from England to Sri Lanka. It isn’t to scale and manipulates space to show the road system. Pictured are stopping places, prominent towns, and mountain ranges.

The Tabula Peutingeriana is also massive at 22 feet in length. At that size, it wouldn’t be useful for a road trip, but with 555 cities and 3,500 place names, it is a chronicle of Rome’s reach.

The map’s geographic information dates back to before at least 79 AD, since you can spot Pompeii. The original map has been lost, but we still have a copy thanks to a monk who reproduced it on 11 scrolls in 1265.

-

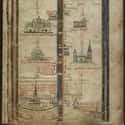

(#4) Itinerary Map By Matthew Paris, Circa 1250s

At first glance, this medieval itinerary map by Matthew Paris doesn’t even look like a map. Instead, it’s a line of castles and buildings crossed by red text and blue waves. The map charts a route from London to the Holy Land, highlighting all the sights along the way. The mapmaker included rivers and hills, alternate routes, and places to stop on a religious pilgrimage.

At the bottom left of the map, you can see Matthew Paris’s depiction of London as a thick city wall ringing a blue church.

Like many medieval maps, this one was not intended to be carried on the road. It was an expensive work of art that may have been used for an imagined pilgrimage - one where the pilgrim never had to leave England.

-

(#5) Anglo-Saxon World Map, Circa 1025-1050

The Anglo-Saxon map, made in Canterbury between 1025 and 1050, contains the earliest known realistic depiction of the British Isles. However, it is almost unrecognizable as a world map, in part because it doesn’t follow many of the conventions of other medieval T-O style maps. Like the Tabula Peutingeriana, it recalls a Roman past by using Roman names for the provinces.

The British Isles are at the bottom left corner of the map, with Jerusalem roughly at the center, again showing the influence of religion on medieval mapmaking. As with many medieval maps, the top is east. Before the 1500s, there was no convention about putting north at the top of maps, and many placed east at the top because Europeans were convinced the biblical Earthly Paradise was in the Far East.

-

(#6) Da Ming Hunyi Tu Map, 1389

In China, medieval mapmakers produced the Da Ming Hunyi Tu, also known as the Composite Map of the Ming Empire, in 1389. The map, a full 15 feet wide, was painted on silk and showed the entire world as known to the Ming. It was also produced at a time of upheaval for China, when the Mongol Yuan rulers had only recently been expelled. In the late 1300s, China balanced between an international outlook, which had been promoted by Mongol rulers, and a more internal focus, promoted by more conservative factions.

Much of the knowledge in the Da Ming Hunyi Tu came from China’s many contacts with Muslim cartographers and intellectuals, and the place names on the western borders of the map are derived from Arabic names.

China would send out the voyager Zheng He to explore the world for nearly three decades in the early 1400s. But after his passing, Ming emperors decided to stop voyages of exploration and focus on China. As they argued, “barbarian” nations offered little of value to China’s prosperity.

-

(#7) Beatus Map, Circa 776

There are multiple versions of the so-called Beatus map, originally included in an 8th-century Commentary on the Apocalypse by Beatus of Liébana. Like the Psalter Map, versions of the Beatus map were included in religious texts in order to illuminate the study of religion.

The Earthly Paradise is shown at the top of the map, with Adam, Eve, and the serpent all making an appearance. But the map also includes fascinating decorative elements. The waters of the world are filled with fish and boats, and palaces also dot the land.

-

(#8) Hereford Mappa Mundi, Circa 1300

The Hereford mappa mundi shows what the simplified T-O structure looks like with more geographical details. This map, made around 1300, has been in England’s Hereford Cathedral for 700 years, capturing a medieval view of the world. Medieval and biblical history mingle on the map, which includes over 500 illustrations of people, animals, cities, and towns; 15 biblical events; and an array of strange creatures, odd people, and mythological images.

The variety in the Hereford mappa mundi points to its intended use: It is a visual chronicle of knowledge, mixing time and space to stun viewers with the scope of the world. And it’s no mistake that the Hereford mappa mundi is housed in a cathedral - it’s also a religious object meant to educate Christians on their place in the world.

-

(#9) Ebstorf Map, Circa 1234

The king of medieval religious maps is the Ebstorf Map, made in the 1230s. It was rediscovered 600 years later, in the 19th century, in a convent in Ebstorf, a small town in Germany. The map takes the typical T-O format, with Asia at the top and Europe and Africa below. It is also the largest known medieval map, measuring nearly 12 feet across. It is so enormous that the map was drawn on 30 goatskins.

The most startling feature of the map, besides its size, is the curious image at the top, sides, and bottom of the map. Look closely, and you’ll spot hands and feet sticking out of the Earth, and a head perched at the top of the map. The figure is Jesus; the world, according to the unknown mapmaker, is literally the body of Christ.

The time, money, and effort that went into creating this medieval map were all erased in 1943 during a WWII air raid on Hanover, when the original map met its end.

-

(#10) Tabula Rogeriana, Circa 1154

This map is perhaps the most worldly. The Tabula Rogeriana - Latin for the Book of Roger - was created around 1154 by a Muslim scholar named Al-Idrisi. He was born in North Africa, educated in Islamic Spain, traveled across the known world, and eventually worked for Roger II, the Christian king of Sicily. In the 12th century, Sicily was heavily influenced by Byzantine, Catholic, Muslim, and Viking traditions. The Normans, former Vikings who settled in France, conquered the island’s Arab rulers and claimed it for themselves. Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, and Normans had all claimed Sicily.

So it's no surprise that Al-Idrisi created one of the most accurate, complete maps of the known world. Al-Idrisi drew on interviews with dozens of travelers, in addition to authoritative texts.

However, the Tabula Rogeriana is also a product of its time, and the best reminder is the fact that the map places south at the top. For Al-Idrisi, the world he knew best - the Muslim territories of North Africa - was to the south, so it made sense to place it at the top.

-

(#11) Catalan Atlas, 1375

In the late 1300s, the most famous mapmakers in Europe were a family of Catalonian Jews. King Charles V of France commissioned the Catalan Atlas to show the most current geographical knowledge in the world, as of 1375. The map is an artistic creation that combines portolan chart geographic knowledge with hundreds of illustrations.

On the world map, you can spot Europeans traveling the Silk Road to China; a warrior elephant with sharpened tusks; the flags of various territories; and strange birds, animals, and people. The map also paints many of the islands, such as Corsica and Sardinia, in gold. Islands were a popular topic of fascination in the late medieval and Renaissance period, and multiple mapmakers created “Isolarios,” or books of islands, that would simply contain maps of different islands. On sea charts, islands were an obstacle to navigation, but they were also linked to the notion of a territorial state.

-

(#12) Medici-Laurentian Atlas, 1351

Some medieval maps are still recognizable today. Africa might appear a bit strange on the Medici-Laurentian Atlas map from 1351, but Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East are all remarkably accurate. That’s because the anonymous maker of this map, probably from Genoa, was trained in making portolan charts.

Portolan charts were used by sailors to navigate the Mediterranean and Black Seas. They required precise geographic knowledge so ships would not get lost. While this expensive and beautifully painted map would not have been taken out to sea, it incorporates knowledge from portolan charts. It also serves as a reminder that religious medieval maps were not produced because mapmakers lacked geographical knowledge, but because the maps served a specific purpose.

New Random Displays Display All By Ranking

About This Tool

In the Middle Ages, people did not have map consciousness. As a new civilized world is being formed, the concept of maps that once existed in the Greco-Roman era is gradually dying out. Although some ancient Roman world maps were preserved until the early Middle Ages, they apparently disappeared as slowly as the dying classical traditions and knowledge, which also led to the production of strange maps at that time.

The knowledge and techniques of scientific mapping were not rediscovered until the 15th and 16th centuries. The random tool shows 12 weird maps of the Middle Ages that you must be interested in.

Our data comes from Ranker, If you want to participate in the ranking of items displayed on this page, please click here.