-

(#5) John Colter is a Hardcore Badass

Colter was considered one of the original, and greatest, Mountain Men... knowing the country and the people inside and out. He was also the one who is credited with being the first white man to have ever seen the volcanic wonders of Yellowstone (a place called "Colter's Hell"). But besides being one of the best, he was also one of the most badass.

In 1809, John Colter, a former member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, was captured by Blackfeet Indians with his companion Potts. While going by canoe up the Jefferson River, Potts and Colter encountered several hundred Blackfeet who demanded they come ashore. Colter went ashore and was disarmed and stripped naked. When Potts then refused to come ashore he was shot and wounded. Potts shot one of the Indian warriors and died riddled with bullets fired by the Indians on the shore. His body was brought ashore and hacked to pieces.

After a brief council Colter was motioned and told in Crow to leave, the legend being that he said to John "How fast can you run?". It soon became apparent that he was running for his life pursued by a large pack of young braves. A fast runner, after several miles Colter was exhausted and bleeding from his nose but far ahead of most of the group with only one assailant still close to him.

"Again he turned his head, and saw the savage not twenty yards from him. Determined if possible to avoid the expected blow, he suddenly stopped, turned round, and spread out his arms. The Indian, surprised by the suddenness of the action, and perhaps at the bloody appearance of Colter, also attempted to stop; but exhausted with running, he fell whilst endeavouring to throw his spear, which stuck in the ground, and broke in his hand. Colter instantly snatched up the pointed part, with which he pinned him to the earth, and then continued his flight."—John Bradbury, 1817.

Colter took a blanket from the Indian he had killed. Continuing his run with a pack of Indians following he reached the Madison River, a distance of 5 miles from his start, and, hiding inside a beaver lodge, escaped capture. Emerging at night he climbed and walked for eleven days to a trader's fort on the Little Big Horn. -

(#4) John C. Fremont Somehow Doesn't Die. Repeatedly.

Where to start with this guy? First off, he's a literal testament to the role of propaganda in history. If you were to only go by what he, himself (although it was actually his brilliant and talented wife who did the actual writing) wrote in his reports/books, you would think him the most heroic, dashing adventurer that ever lived. But the most awesome accounts of Fremont's explorations come from the letters of his topographer, a meticulous german named Preuss.

But lets start at the beginning. Frémont first met Kit Carson (yes, that Kit Carson) on a Missouri River steamboat in St. Louis during the summer of 1842. Frémont, a was preparing to lead his first expedition - one which he got solely through the political connections of his wife and Very Important Father in Law - and was looking for a guide to take him to South Pass. Carson offered his services, as he had spent much time in the area. The five-month journey, made with 25 men, was a success, thanks to Carson's skills and knowledge. It was during this expedition that a large amount of important topographic information was gathered, almost all of it at the hands of Pruess - a man whom Fremont saw as something of a reliable Man Friday and who did most of the work. Pruess's letters tell a story of a gloomy man chained to, and annoyed by, "that childish Fremont". In a hilarious story, Fremont and his party crossed the Rockies over South Pass - a wide sandy saddle that lacked any of the romantic drama that Fremont was expecting, and disappointed him so much, he didn't even take any topgraphical observations at the crest. So, a few days later when they arrived at the Wind River Range, Fremont decided to climb what he arbitrarily decided was the tallest peak in the Rockies. The peak he selected, which has been named after him, was only 13,785 feet high... lower even than Gannett Peak only 5 miles away and lower than 55 other mountains in nearby Colorado. BUT, he was convinced this was the loftiest of all, and so dragged his party with him to make this "historic" climb. This climb was to be important to Fremont and to his career and image as "the Pathfinder", but to listen to Preuss tell it, it was more comic than heroic.

"The leader, Carson, walked too fast. This caused some exchange of words. Fremont got excited, as usual, and designated a young chap to take the lead - he could not serve as guide, of course. Fremont soon developed a headache, and as a result we stopped soon afterwards, about eleven o' clock. He decided to climb the peak the next morning, with renewed strength and cooler blood."

The next day they again attempted to make the summit, but the party soon began to straggle, and Preuss found himself alone in the snow 1,000 feet below the summit. Fremont had become "peckish" and had returned to camp. Preuss couldn't find his own way up, so he took some readings and returned to camp himself. He wrote, dripping with sarcasm: "I could not keep from remarking that in such an undertaking some preparations for sleeping, eating and drinking would not be altogether amiss and might, indeed, be more conducive to success."

They finally made it to the top on the 15th, and it become firmly marked as a legendary climb by Fremont.

On the return trip, they cam across the Platte River, which was in flood at the time. Here, he divided his men, sending the larger group overland while he, Preuss and 5 others shot the rapids, using a raft he had brought along for just such an occasion. Shortly after leaving shore, the boat capsized in the rapids and many of the scientific records and data they had gathered were lost. These stories are perfect to describe a man who, for most of his career of "exploring", relied on those around him to do the work and when using his own common sense, display nothing of the sort. He had the most amazing string of good luck that could ever be ascribed to someone in a career as dangerous as the one he undertook. Many of his expeditions were blessed with mild winters and good weather. If, at any point, even a middling blizzard had hit him, his entire party would have been killed. One one expedition, he (well, his men) dragged a massive carriage-mounted Howizter that fired 12 inch cannonballs along "in order to intimidate the indians", despite the fact that leadership in Washington freaked out when they heard that a supposedly peaceful scientific expedition was carrying along something that could enrage either Mexico or Britain. They sent word to him to leave it behind, but he never got the message. He ended up abandoning it in the snow high in the mountains, but not until after he'd used it to "hunt" buffalo by firing it indiscriminately into herds.

Fremont was a man who lucked into his marriage, lucked out of countless brutal deaths at the hands of weather that never hit him, indians that somehow missed him, and political blunders that never seemed to have repercussions.

But.

In the end, it all caught up with him. After a failed run for the Presidency, a string of disastrous bad luck hit him during the civil war where he served as a bungling, impolitic general who was stripped of his command by Lincoln. Poor business judgement turned the wealth he had accumulated through his career as an explorer into dust. At the end of his life, it was his awesome wife who supported them with her writing. And he died in 1890 in a boarding house.

I wonder what happened to Preuss? -

(#1) Cabeza de Vaca Stars in His Own Real Life Movie

In 1527 Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca left Spain as a part of a royal expedition intended to occupy the mainland of North America. The first thing that happened, after they got past the cakewalk of sailing across the Atlantic Ocean, was a hurricane off Cuba. But, no prob. They got a new boat (I'm sure the natives were happy to send them anywhere but there) and they landed near the current location of Tampa Bay in Florida where the leader of the expedition, Narvaez, claimed the land for Spain. Hurray! But this was where it got kind of bad. Despite the fact that they didn't really know where the F they were, Narvaez wanted to split up ... take some guys by land and some by sea ... because, you know. Gold. Gold was there, somewhere! De Vaca thought this was a bad idea, but he was overruled by his boss and ended up marching through Florida, promptly getting lost.

After several months of fighting natives and swamplife, the party reached Apalachee Bay with 242 men. They hilariously believed they were near Mexico, but well, if you look at a map (I'll wait) you will see that Mexico is not adjacent to Florida. The men were starving, wounded, sick, and lost in swampy terrain, but came up with a plan for escape. In the part of the movie that would require a montage, probably with "Eye of the Tiger" playing, they killed their horses, melted down stirrups, spurs, horseshoes and other metal items, and fashioned a bellows from deerhide to make a fire hot enough to forge tools and nails. They then MacGyvered five primitive boats to use in search of Mexico.

Cabeza de Vaca got to be in charge of one of these vessels, each of which had room for only 50 men. Depleted of food and water, they followed the coast westward, until they reached the Mississippi River. The current swept them into the Gulf and the five rafts were separated by a hurricane (yes, another one), some lost forever, including that of Narváez.

Two rafts, including Cabeza de Vaca's, wrecked near Galveston Island. They made an attempt to fix the rafts, using what remained of their own clothes, but they lost the rafts to a large wave. Yikes. Sorry, guys, but thats... kind of a funny (but SAD!) visual. As the number of survivors dwindled rapidly, they had the luck of being enslaved for a few years by various (yes, various... as in, they got passed around like the last joint around the campfire) Native American tribes.

By 1532 (thats 5 years since he left Spain on this fabulous Cruise From Hell), only three other members of the original expedition were still alive -- Alonso del Castillo Maldonando, Andrés Dorantes de Carranca, and Estevan, an African slave. Through this particularly unfortunate chain of events, Cabeza de Vaca ended up exploring quite a bit of what is now the Southwest US and parts of Northern Mexico. He traveled on foot all the way down the Gulf of California coast to what is now Sinaloa, Mexico, over a period of roughly eight years. He lived in conditions of abject poverty and, occasionally, in slavery.

After finally reaching the colonized lands of New Spain where he encountered fellow Spaniards near modern-day Culiacán, Cabeza de Vaca went on to Mexico City. From there he sailed back to Europe in 1537.

And speaking towards his character, he ended up being a major advocate for Indian rights despite being a slave to various tribes for so long. It got him in a lot of trouble with the authorities, and was arrested for poor administration in 1544 and returned to Spain for trial in 1545. Although eventually exonerated, he never returned to the colony.

He died poor in Valladolid around the year 1558, but if you think about it from History's point of view, he was the winner in the end. The report he wrote of his adventures is considered a classic of colonial literature, and his name is still remembered today. -

(#3) Joe Walker Pretty Much Rules

At fifteen, Joe Walker and his older brother had fought with Andrew Jackson at the battle of Horseshoe Bend. Yes, that's pretty awesome. I was making mix tapes of Duran Duran when I was fifteen. Walker, grown up, only got more awesome. He was 6'4" with super long rockstar hair and a big beard. He was also someone who could find his way through the untracked American West without being killed by:

1)Indians

2)Bears

3)Starvation

4)Brutal Elements

5)More, Different Kinds of IndiansWhat made him stand out from the other guys who could do those same things, was that he was a leader. With things like "foresight" and "planning abilities" and, most importantly, "people skills". These things made him into THE MAN at the time. And so, when this ex-army guy, Bonneville, decided he wanted to find a route to the Pacific (there wasn't one at the time, really... I mean, Lewis and Clark did it, but they didn't exactly take a route that wagons could go) he flipped open the yellow pages to the full page ad of Joseph Walker: Awesome Dude.

Walker was everything you wanted in a leader into unknown country. He knew the wilderness and he knew the indians. Most importantly of all, he was prepared. Prior to moving into the Salt Lake basin the party had stopped on the Bear River, where they hunted until each man had 60 pounds of dried and jerked meat in his pack. Ordinary mountain men would have neglected this precaution; they were prone to gorge when the hunting was easy and starve later.

They headed out, and his first order of business on arriving in the Great Basin was to seek out a band of local indians, a Shoshoni people, to ask for directions. Using the information he got, the party set out due west. They began to encounter Paiute Indians, a stone age tribe that lived by gathering roots, beetles, lizards and hunting small game.

The "Diggers" (as they were called) were unfamiliar with white men and their equipment. So while the trappers searched out meager supplies of beaver, the Indians stole whatever they could get their hands on whenever they could. Walker tried to keep tempers down, but several of his men disregarded his counsel and ended up killing several of the Indians who had stolen some of their traps. Now the Diggers were not just greedy for more cool stuff, they were pissed. They soon had the party surrounded with numbers between eight and nine HUNDRED.

Walker ordered the men to make a quick fortification out of their packs, which they huddled behind. And the Indians marched straight at them... but then, within about 150 yards, they all sat down on the ground (PSYCH!), and sent five of their chiefs to inquire whether Walker's people would come and smoke with them. Walker, no fool, refused. Instead, he did a live demonstration of what a rifle was capable of (the Diggers had never seen one) on some unfortunate ducks. This, somehow, did not translate. And when the trappers started up their journey the next morning, the natives attacked. Walker, having exhausted other options, opened fire. 39 Diggers were killed, and the threat vanished just like that.

The party then began working their way into the Sierras up a river that later was named after Walker and, unable to find anything that looked like a pass, started probing upward for whatever they could find. The climb, encumbered by fields of boulders, snow-choked gulches, and sheer–walled canyons, had them starving and exhausted. Walker averted mutiny only by allowing the men to butcher and eat several of the horses. Seventeen more would be slaughtered before they were to find regular game again. Reaching the summit, over icy rock walls and cliffs, took almost three weeks and the western descent offered little relief.

Moving down, the Walker party became the first known white men to look into the Yosemite Valley. A place was found where the horses could be lowered down on ropes and, after fighting their way through the boulders, Walker discovered an Indian trail. By the end of October 1833 the party came into view of the Pacific Ocean.

Before pushing on to Monterey, the capitol of Upper California, camp was ordered near the mission at in San Juan Bautista. Walker, through the mediation of an American ship captain, secured a passport, which displayed his respect for the foreign sensibilities (remember that California was Spanish at the time), ensured the welcome of the Spanish governor. This was something that many other explorers of the time never seemed to figure out. Politeness in a foreign nation counts. The Walker party, returning by a different, less-difficult route, arrived at the Bear River rendezvous on July 12, 1834, without loss of a single trapper, having discovered the Pass that was destined to become one of the main entry points for emigrants bound for California.

In 1862, 64 years old, eyesight failing but still remarkably fit, he was guiding a party of gold prospectors through New Mexico when they ran low on water. Walker assured them he had passed that way years before and knew the whereabouts of a good spring to the southwest. And on the third day at the foot of a parched unpromising mountain, Walker told them to start climbing and that near the summit they would find a flat rock and the spring. He also told them to watch out for Apaches. The spring was found exactly as he described it. He was also right about Indians, as the same day they found three white men hanging by their ankles from a pinion tree.

And lastly, a final testament to this man's hardcore badassery, in 1863 he led another prospecting party into what came to be known as Horse Thief Basin in Arizona. They began to run low on food and water. Walker, though nearly blind at this point, set off with a single man for the trading post at La Paz, 200 miles away. They were jumped by a pair of Mexican outlaws who took his companion by surprise. Though he was unable to see clearly, Walker’s instincts and reflexes were still intact and he drew and fired, driving the outlaws away.

Joe Walker died on October 27, 1876 at the age of 78. He was buried at Martinez,

California with the following epitaph: "BORN IN ROAN CO. TENN.DEC. 13, 1798. EMIGRATED TO MO. 1819.

TO NEW MEXICO, 1820. ROCKY MOUNTAINS, 1832. CALIFORNIA, 1833. CAMPED AT YOSEMITE, NOV. 13,

1833." -

(#2) Hugh Glass IS the Terminator

Hugh Glass had already been in the Western wilderness for several years when he signed on for an expedition up the Missouri River in 1823 with the company of William Ashley and Andrew Henry (these guys were players in the ridiculously HUGE industry of trapping at the time). The expedition went up the Missouri as far as the Grand River near present-day Mobridge, South Dakota. There Glass along with a small group of men led by Henry started overland toward Yellowstone.

At a point about 12 miles south of Lemmon, SD, now marked by a small monument, Glass surprised a grizzly bear and her two cubs while scouting for the party. He was away from the rest of the group at the time and the grizzly attacked him before he could fire his rifle. Using only his knife and bare hands, Glass wrestled the full-grown bear to the ground and killed it, but in the process he was badly mauled and bitten.

His companions, hearing his screams, arrived on the scene to see a bloody and badly maimed Glass barely alive and the bear lying on top of him. They bandaged his wounds the best they could and waited for him to die. But the party was in a hurry to get to Yellowstone, so Henry asked for volunteers to stay until Glass was dead and then bury him (kind soul). John Fitzgerald and Jim Bridger (yes, THE Jim Bridger, but he was only a kid at the time) agreed and immediately began digging the grave. But three days passed and Glass was still alive. Fitzgerald and Bridger began to panic as a band of hostile Indians was seen approaching. So they did what anyone would do... they grabbed all his stuff (knife, rifle, etc) and dumped him, still alive, into the open grave. They threw a bearskin over him and shoveled in a thin layer of dirt and leaves, leaving Glass for dead.

But, still, he did not die. When he regained consciousness he found that he'd been Punkd'. He was alone and unarmed in hostile Indian territory. He had a broken leg and his wounds were festering. His scalp was almost torn away and the flesh on his back had been ripped away so that his rib bones were exposed. The nearest help was 200 miles away at Ft. Kiowa. His only protection was the bearskin hide Bridger and Fitzgerald had kindly left him.

Glass set his own broken leg and on September 9, 1823, began crawling south overland toward the Cheyenne River about 100 miles away. Fever and infection took their toll and frequently rendered him unconscious. Once he passed out and awoke to discover a huge grizzly standing over him. According to what is probably legend (but who the hell knows?), the animal licked his maggot-infested wounds which would probably have saved Glass from further infection and death. Glass survived mostly on wild berries and roots and what he could find on the ground (because, remember, CRAWLING). On one occasion he was able to drive two wolves from a downed bison calf and eat the raw meat.

It took Glass two MONTHS to crawl to the Cheyenne River. There he built a raft from a fallen tree and allowed the current to carry him downstream to the Missouri and on to Ft. Kiowa, a point about four miles north of the present-day Chamberlain. After he regained his health, which took many months, Glass set out to kill the two men who had left him for dead, and he found them.

However, unlike the actual Terminator, he didn't kill either of them. When he found Bridger at a fur trading post on the Yellowstone River he didn't kill him because Bridger was only 19 years old. And later, when he found Fitzgerald, he didn't kill him either because Fitz was in the Army at that point.

Frankly, I think it's a testament to his character that he left them alive. According to Glass, he survived his ordeal soley on thoughts of revenge. To then show mercy when given the opportunity speaks of a man who was both resilient and thoughtful. There was a reason he became a legend of his time. -

(#6) Jed Smith Crosses the Mojave Without Air Conditioning

Ever been to Vegas? I bet you didn't walk.

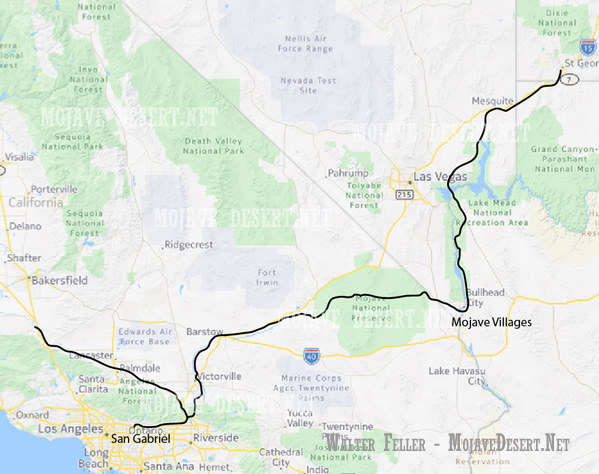

In what was to be his first trip across the Mojave, Jed Smith and his band wandered along the eastern Great Basin Desert through what Smith called, "the land of starvation." Crossing the Colorado River and into Arizona, He traveled south along the mountains until reaching a Mojave Indian village (near Needles, California).

If you haven't been there... it looks like this:

Jed wrote:

"The Salt Plain I had passed during the day was about 15 miles long and from four to six miles wide. Entirely Level and destitute of vegetation. Presenting a surface of sand the most beautiful salt was found in many places and within two or three inches of the surface. I ascertained that although the salt was found in a layer it did not extend throughout the plain. In passing the plain pieces of the salt were frequently thrown out by the feet of the horses. The Layer was about 3/4 of an inch thick and when the sand was removed from it I found the salt pure white with a grain as fine as table salt."

Salt! That's neat. Right? Can you drink that?

"The next day W S W, 8 or 10 miles across a plain and entered the dry bed of a river on each side high hills. Pursuing my course along the valley of this river 8 or 9 miles I encamped. In the channel of the river I occasionally found water. It runs from west to east alternately running on the surface and disappearing entirely in the sands of its bed leaving them for miles entirely dry."

Jed came in contact with Mojaves at a Southern Paiute settlement in Utahsas where its members arrived, bedraggled and almost starving, after a long and difficult trip through the mountains. Since they were carrying no beaver skins nor any other signs of being trappers or fur traders, they met with traditional Mojave hospitality, and were fed, guided first down the Virgen River to North Mojave rancherias, and then to the main Mojave settlement in the Mojave Valley. Smith was provided with Mojave guides when he left, and went on to the San Bernardino Valley and Mission San Gabriel, where his welcome was less than warm. The two Mojave guides were imprisoned by the mission fathers, and one of them sentenced to be hung for the crime of bringing a foreigner into Spanish territory, although Smith wrote later in his journal that the priest at the mission had been able to secure a pardon for the man.

He returned via a different path (I can't imagine why!) (map credit - Walter Feller mojavedesert.net)

(map credit - Walter Feller mojavedesert.net)

New Random Displays Display All By Ranking

About This Tool

In the early days of the founding of the United States, the government used various means to expand its territory to the west. The most prominent of these is the land development policy, as well as vigorously developing transportation and supporting education. The exploring of the American West has lasted for a century, and the history is much more complicated and cruel than what we know from literary works and books. True western history is complex and diverse.

At the end of the 18th century, a large number of immigrants moved to western America for different reasons, which was an aggressive act to expand the territory, and a large number of Indians were massacred. The random tool shares 6 brutal stories in American West history.

Our data comes from Ranker, If you want to participate in the ranking of items displayed on this page, please click here.